8:32. You might see it scrawled in a dusty car window or etched into the sand on the beach. On a bumper sticker or a cap, or on the t-shirt front of a passer-by. It’s a symbol of truth, freedom and resistance. Resistance to what? We’ll get to that.

Readers with a religious education may have clocked its meaning already, though the movement that has adopted 8:32 is a broad church including the religious, the spiritual, and those with no faith or religion to speak of. Turn to John 8:32 in the Bible, and there it is.

“Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

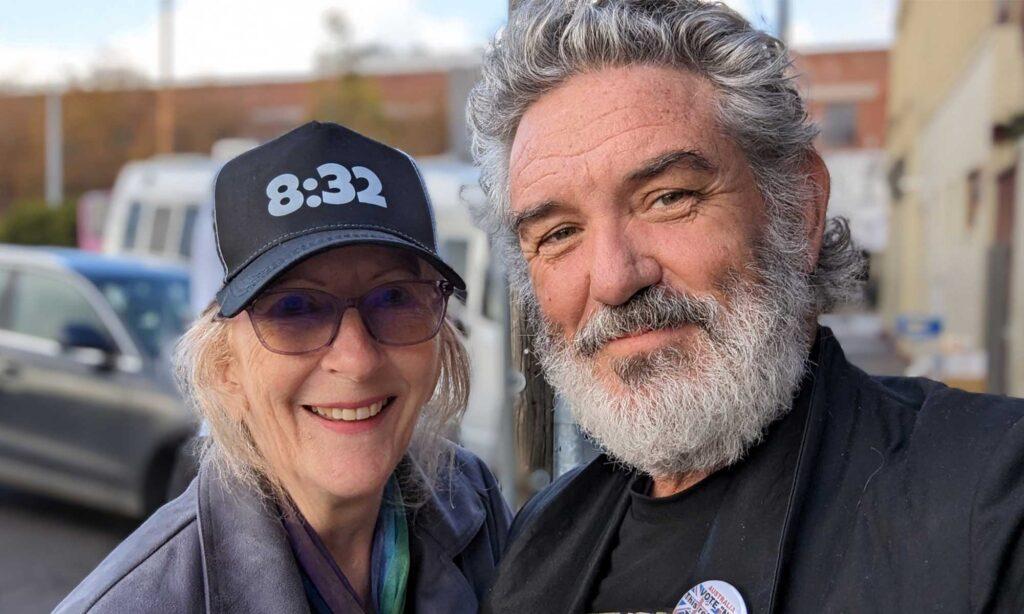

Jesus said it first a couple of thousand years ago, though in a time of confusion, conflict and totalitarian creep, this age-old call to truth and freedom is pertinent as ever. Today, it’s activist and citizen journalist Michael Gray Griffith sharing the message.

Griffith is a well-known character in the ‘freedom movement’, the collective term for Australians from all walks of life who share the common belief that freedom is worth fighting for. There is an old saying that the standard you walk past is the standard you’re willing to accept. For Australia’s freedom movement, the government COVID response was a line in the sand that they are simply not prepared to walk past. Instead, they resist, and Griffith is standing on the frontline.

Hailing from Melbourne, Victoria, Griffith was a playwright with his own theatre company until first lockdowns, and then proof of vaccination restrictions choked his business and career. “When they said they were going to segregate audiences, I put up a post saying we wouldn’t do that, and I was effectively cancelled,” says Griffith.

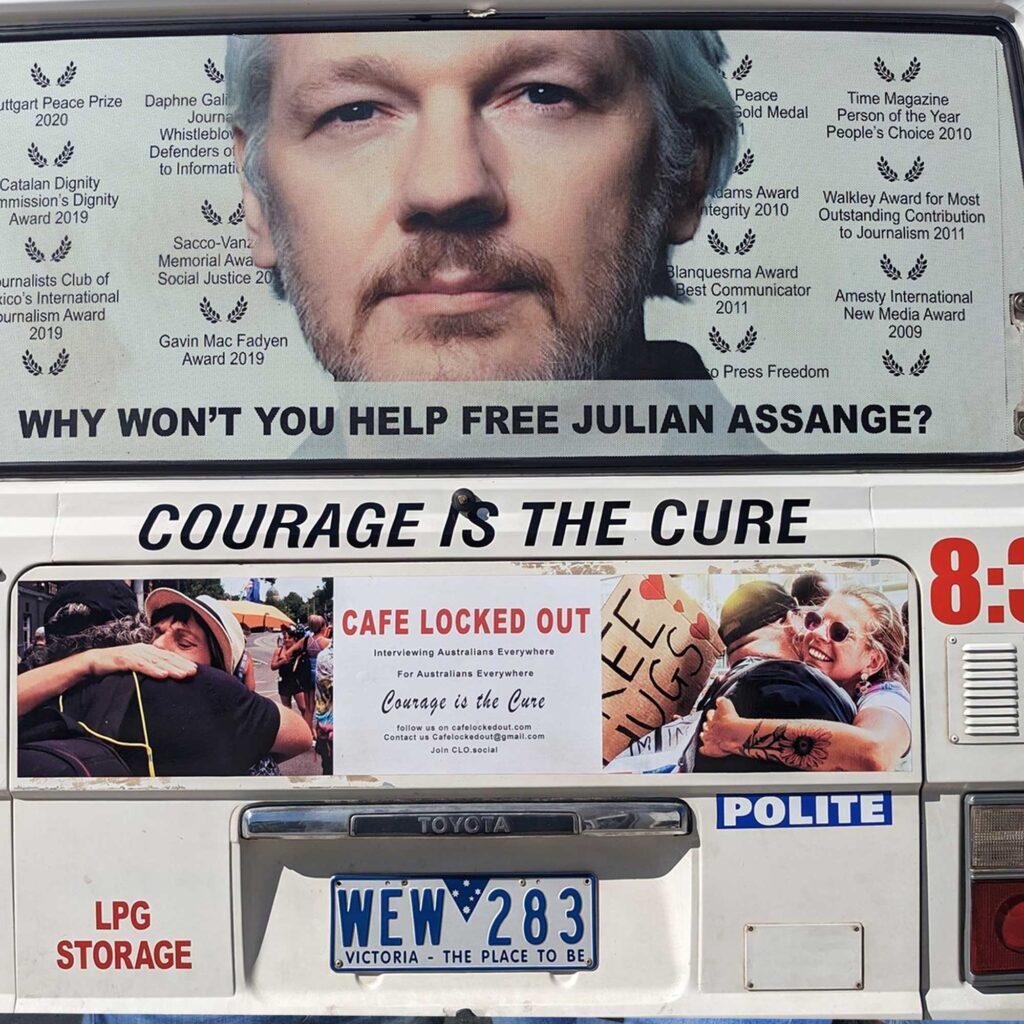

Not one to lay idle, Griffith started a Facebook page called Café Locked Down, where he would interview Australians about their lockdown experiences. The page grew quickly, and the Café spread to other platforms. With the introduction of segregation policies, Café Locked Down was renamed Café Locked Out, and Griffith took to the road in ‘Florence the Freedom Bus’, named in honour of his mother. He’s been on the road since, collecting stories and reflecting back to Australia who and what we are.

Talking with people all over the country, Griffith gets the feeling that the Australia he grew up in is all but gone. When Griffith talks about resisting and fighting for freedom, this is the Australia that he is thinking of. “This hate speech that has been allowed to be used to describe the freedom movement – ‘anti-vaxxers’ – all we’re talking about is the freedoms we were born with. Freedoms which have been eroded in my lifetime,” says Griffith. “Through our compliance we’ve allowed ourselves to be violated,” he says. “We have acted like serfs.”

Griffith, who is 57, says he feels a responsibility to defend the freedoms that he has enjoyed so that they can be handed to the next generation. “It’s not my job to give them away so that I can go and have a latte in a café,” he says dryly.

It was in his effort to resist the Victorian government’s curtailment of civil liberties that Griffith witnessed things he never imagined possible in Australia. Griffith attended numerous freedom protests during Melbourne’s famously harsh COVID lockdowns and restrictions over 2020 and 2021, where he saw, “riot police in armoured vehicles opening fire on anyone they thought was protesting.” Police were equipped with baton round launchers, which fire ‘rubber bullets’ and pepper ball (capsicum spray) firearms. On one occasion, a policeman shot Griffith with a rubber bullet while he was walking in a protest. The bullet broke his hand.

By September 2021, the Melbourne protests had become increasingly chaotic, but Griffith felt an obligation to be there. “I thought, ‘this is my generation who dropped the ball’, so I stuck it out.” In the same week that he was shot in the hand, Griffith was present at the infamous Shrine of Remembrance protest, from which footage of an advancing police line firing on protestors shocked viewers around the world. On that day, Griffith was “brutally beaten” and arrested for sitting, arms linked, with other protestors at the memorial.

Photographer Matthew Lawson met Griffith at the protests, and he too was shocked by the police brutality he witnessed. “They tended to go straight to pepper spray, using batons or pushing people on the ground, they weren’t really using moderate de-escalation tactics,” he says, recalling that a kid of around 11 years old got a “full face of pepper spray” at one protest.

Lawson was shot by police at close range with pepper balls and rubber bullets while trying to de-escalate tensions between police and protestors on 21 August 2021, and he’s still shaken. “You trust your police,” he says. “You never expect the police to open fire on you, not in Melbourne, not in Australia.” Lawson came away with a tear in his abdomen wall and a large hematoma, and he has now developed a hiatus hernia from the injury, as well as daily heartburn.

The crushing of dissent was not just happening at face-to-face protests. Griffith says that the aggressive censorship of dissent online also surprised him. “Many of us suddenly got Facebook bans all at the same time. It was incredible. We were getting censored for asking questions.”

Lawson noticed a disconnect between what was happening on the ground, and what was reported on the news. “The first time I went to a protest, I saw people playing guitar and singing together. Then went home and watched the news coverage and they said that it was a Neo-Nazi protest, and I realised none of it was true.

For both men, these unsettling experiences have changed their perception of who we are as a country, and where we’re headed. “People said they were fine with giving their freedoms away temporarily and that we’d get them back again, but history shows that that’s not how it works – once you give them away, you only get handed back privileges, which can be withdrawn at any time,” says Griffiths. Lawson agrees that we’re heading in a troubling direction. “It’s crazy. In a democracy, you should be able to speak, you should be able to protest.”

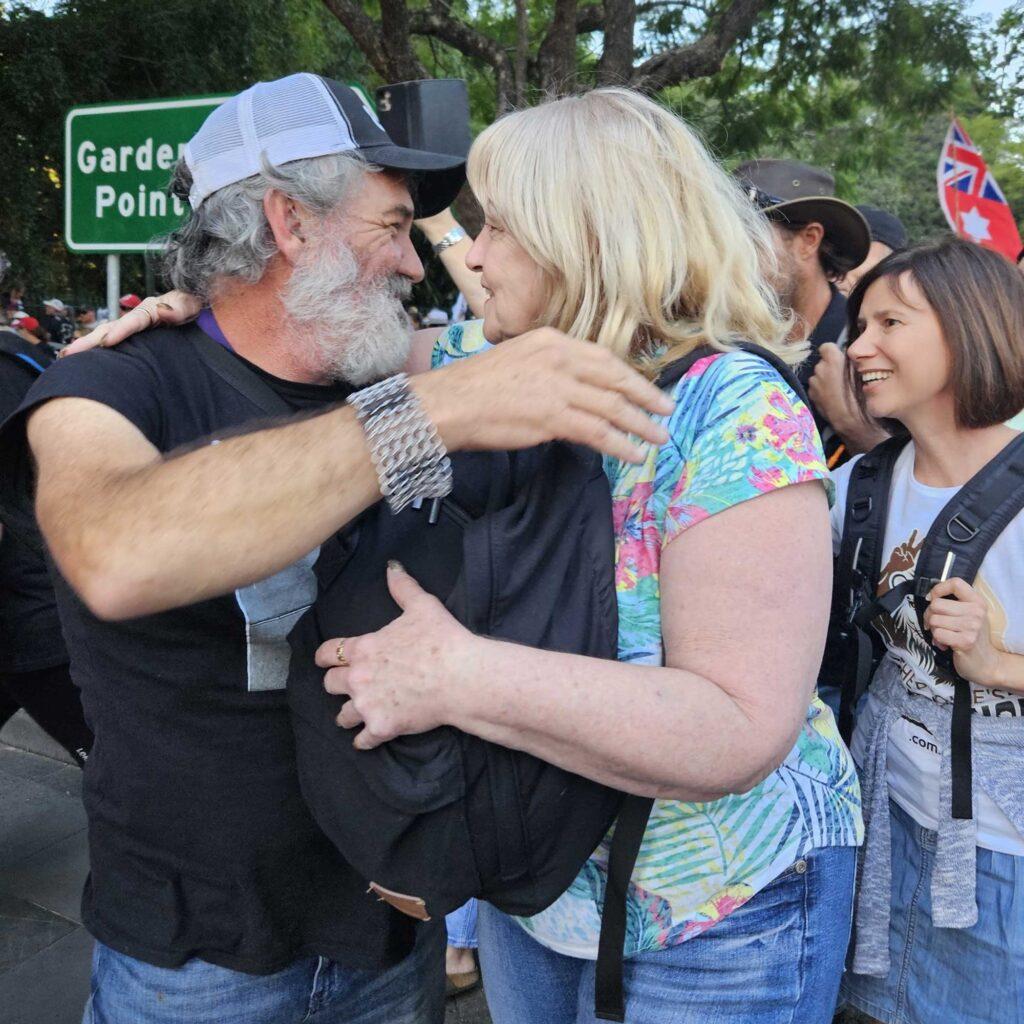

After this tumultuous period, Griffith hit the road. “We were trying to see if there was resistance all over Australia,” he says, “and there was.” However, due to isolation – this was while unvaccinated Australians were still largely ‘locked out’ of much of the economy and society, and travel restrictions were off and on – the resistance was dispersed. Particularly in regional areas, some were feeling the loneliness of swimming against the stream alone.

“We needed a unifying symbol,” says Griffith. “Something you could spot on a car bumper or on a t-shirt, unique to our movement. I put a call out for suggestions and a woman named Arianne suggested 8:32.” Griffith hopes that just seeing the symbol will give people hope that they’re not alone, and that it might make people think a bit deeper.

When asked for his interpretation of 8:32, Griffith responds thoughtfully. “There are three fundamentals. In a free democracy you must have freedom of choice, freedom of speech, and freedom to be yourself. I feel that if you truly know yourself, you have a lot more to offer society.” Griffith’s commitment to upholding the freedom to find and become one’s ‘true self’ is a value that groups from both sides of the political divide advocate for. The catch is that, as Griffiths explains it, the three fundamentals are inter-dependent. You can’t have self-actualisation without freedom of choice and freedom of speech.

Lawson says that he found freedom by turning the television off. “I think once you break away from the narrative they’re feeding you, you break away from the control and you find freedom of thought.”

“People just want to hear from people who are earnestly looking for the truth,” says Griffith. “They want anything they think is real. It’s not about being perfect or put together. It’s the Wild West of new journalism,” he says, referring to the growing movement of citizen journalism rising to fill the informational gaps that the traditional news media used to cover, but no longer does. “A society that’s trying its best to build a culture on the truth is a better society, and a healthier society to leave in next generation. That’s what I’m fighting for.”

Like nomadic sages of Biblical times, Griffith leaves off with an illustrative metaphor. “COVID was a great bushfire. It burned our culture to the ground. But after the destruction of a bushfire, latent seeds germinate, and new shoots push out of the ground, creating something new.” These shoots, Griffith muses, are the freedom movement, creating something new out of the blackened ground. “I believe we are the new architects of Australia’s future.”