The Australian Constitution is the founding document of the nation, which provides the basic rules of how government is formed and the processes by which it should govern.

The fundamental law within it, however, differs starkly to the reality of how the nation’s governing body operates on the ground.

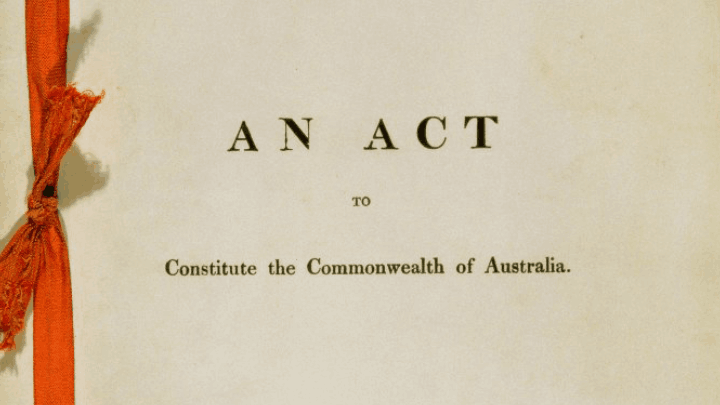

The difference between the governing rules within the Constitution, which was established via a 1900 Act of British Parliament, and how government actually functions is attributable to the use of conventions: unwritten rules, not laws, which are an accepted way of doing something.

The scandal that erupted last year around former PM Scott Morrison having had the governor general David Hurley secretly swear him in as the dual administrator of five ministries that weren’t his own, exposed the pitfalls of operating under such conventions, which can easily be corrupted.

And another reason the Constitution has been a focus of late is that a movement formed in opposition to pandemic restrictions, initially turned to the document as a means to defend its rights against the imposition of strict health measures, only to find that it doesn’t actually protect them.

Establishing parliament

The Australian Constitution has eight chapters. The first creates Australian parliament and consists of five parts split into sixty sections.

The first part establishes legislative power, which rests within federal parliament: a body comprised of the Queen, the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The Queen, as head of state, is empowered to appoint a governor general as her Commonwealth of Australia representative.

Yet, the reality of this today involves the PM appointing a GG. And via convention, the prime minister can sack the governor general, and the GG can sack the PM.

Part two brings the Senate into play, with each state electing six senators. While part three creates the second lower chamber of parliament: the House of Representatives, which has about twice as many members as the upper, with its numbers for each state depending on population.

The powers of parliament are set out in part five. Section 51 provides a comprehensive list of 34 matters that federal parliament has the power to enact laws in relation to, which include trade and commerce, tax, postal and telephone services, defence, quarantine and marriage.

Controversially, part five not only permits the GG provide royal assent to see legislation made law, but the official can also return a proposed law to parliament and recommend amendments, while the Queen retains the power to intervene and disallow any law passed within the last 12 months.

Two further arms

Whilst the first chapter establishes the first arm of government, parliament, the next two chapters provide for the two other arms: the executive and the judiciary.

However, in terms of the executive, chapter two makes no mention of the prime minister or cabinet, as these entities are by convention.

Rather, in the Constitution, executive power is “vested in the Queen” and exercised by the governor general, who is then empowered to appoint ministers from parliament to administer departments. And the GG is also made commander-in-chief of the Australian Defence Forces.

The third chapter provides the framework for the judiciary, including the High Court of Australia, which holds ultimate judicial power. The court has the ability to hear appeals against “all judgments, decrees, orders, and sentences” made in any Australian jurisdiction.

And the governor general further holds the ability to appoint judges, even though the actual selection is made by the attorney general as another matter of convention.

A dearth of protections

Chapter four of the Constitution sets out the broad rules for trade and finance, while chapter five spells out the powers of the states.

Section 109 stipulates that when there is an inconsistency between federal and state law, the federal law stands, and the state law becomes invalid.

In terms of rights protections, unlike the Constitution of the United States, there are only a handful of rights protected in this nation’s founding document.

Section 41 establishes a right to vote for all citizens, while section 51(xxxi) provides that the acquisition of property must be done on just terms, and the right to trial by jury is enshrined in section 80.

A provision to ensure free interstate trade across the continent is contained in section 92 of the Constitution, while the grounds for freedom of religion are established under section 116.

And the High Court found in two separate judgements over 1992, that, as the Constitution establishes rules for citizens to vote on members of parliament, these provisions imply a right to freedom of political communication, so that informed decisions can be made.

But the High Court didn’t find that the implied right constitutes personal freedom of speech, rather it determined that the protection places restrictions upon the executive and parliament in stymying public discussion of government, its institutions and politics.

Reform necessitated

The final chapters of the Constitution set out rules for admitting new states into the Commonwealth and some miscellaneous powers, as well as providing that for any changes to be made to the founding document, the citizenry must take part in a referendum, or national vote, on such reform.

In terms of governing the nation, however, the final chapters provide no more clarity than earlier ones, with the framework of Queen, as head of state, operating via her representative, the governor general, in conjunction with a bicameral parliament being all that’s established by the document.

And it’s these bare bones foundations the Constitution presents that has left institutions, such as prime minister and cabinet, to function via convention, which has then led to a situation where a former PM was able to exploit the gaping holes left.

The Morrison scandal sparked calls for the running of the country to no longer rest upon mere formalities, but instead statutory laws be passed that clearly define institutions and how they operate, or in terms of establishing a republic, the call is for an overhaul of the entire Constitution.

As former federal Labor minister Barry Jones set out in a recent Saturday Paper article, he supports constitutional reform, so that the founding document defines Australia as a democracy and sets out that the head of state be an Australian citizen and that the PM and cabinet hold executive power.

And as for those concerns about a lack of rights protections at the federal level in this country, the Australian Human Rights Commission is about to release a comprehensive report arguing the case for a national Human Rights Act that would enshrine a multitude of protections in law.