LOS ANGELES – Officer Mike Martinez has a mental map of all the security cameras in the small Californian town of Rialto.

Driving around town, he can pick out even the most hidden surveillance devices, from the small cameras keeping watch on a corner gas station, to a row of devices guarding the wall of a warehouse a few blocks away.

“This is not about Big Brother watching you,” he told Context from behind the wheel of his black and white SUV police cruiser. “This is about public safety.”

For the past year Martinez has been trying to convince owners of private surveillance cameras to enroll in a city-run program that can share control of those cameras with the police.

In 2019, the city of 100,000 became one of the first on the U.S. West Coast to roll out technology from Fusus, a U.S. security tech company that aims to boost public safety by making it easier for police to access privately owned surveillance cameras.

In 2022 the company told surveillance research firm IPVM that it had helped network more than 33,000 individual cameras in over 2,400 distinct locations around the U.S.

In Rialto, the police have access to over 150 livestreams across restaurants, gas stations, and private residential developments – a number they are hoping to increase through Martinez and others’ outreach.

Fusus technology is being operated in over 60 different cities and counties across more than a dozen states, by police departments, school districts and sheriffs as part of public safety initiatives, according to public records requests and announcements seen by the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Since the beginning of the year, over a dozen small and medium-sized cities and suburbs have introduced or expanded their use of Fusus tech, fueling local debate about the balance between city dwellers’ privacy and public safety.

According to Fusus, police chiefs and city leaders, hooking public and private cameras into one surveillance system is key for modern police working, allowing officers to have greater “situational awareness”, and making it easier for them to retrieve evidence.

For critics, such a system tramples the privacy of residents, and risks handing police tools that are easily abused.

“This surveillance is happening in areas that are already over-policed – and it does not keep us more safe,” said Nia Sadler of advocacy group Triad Abolition Project, which campaigned unsuccessfully against the use of Fusus tech in Winston-Salem, North Carolina last year.

Sadler said the surveillance cameras in Winston-Salem tend to be concentrated in areas where Black residents like themselves live – a common critique among local activists who object to the use of Fusus tech.

Albert Fox Cahn, founder of the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project in New York, said Fusus is helping smaller American communities mimic the surveillance models of big cities “bringing the surveillance city to the suburbs”.

That, he and other critics say, brings with it myriad privacy and civil rights concerns.

“Fusus takes surveillance tools that are constitutional on their own, and aggregates them into the kind of persistence tracking that is blatantly unconstitutional (when used by government bodies).”

Fusus did not respond to multiple requests for comment over the past three weeks. In a report published on its website, the company says its technology provides “greater safety with an eye to privacy”, citing “robust community protections”, including activity logs that track how police use the tool.

‘Real-time crime center in the cloud’

For over a decade, larger U.S. cities have been building integrated monitoring programs that often link public and private cameras to allow police to keep tabs on various locations.

In 2012 New York City launched its Domain Awareness System with Microsoft, and in 2016 Detroit launched Project Greenlight in partnership with Motorola – both programs linking public and private camera networks.

But such systems have often been out of reach for smaller communities, said Sean Patton, a product manager with IPVM.

“So Fusus has come in and grabbed significant market share,” said Patton, who authored a 2022 report about Fusus, which was buoyed by a $21 million investment from police body-camera maker Axon in 2022.

In a podcast interview in March for Business Radio, Fusus CEO Chris Lindenau said the goal of the company was to build New York-style surveillance systems for thousands of smaller police departments around the U.S.

With annual subscription fees starting under $20,000 Fusus provides cities with what it calls a “real-time crime center in the cloud”, while New York’s system cost as much as $40 million to set up, according to local media.

Business owners are then encouraged by the police to buy hardware that integrate their onsite cameras with the police network – allowing police to call up the private camera network on their own phones, tablets, and desktops.

The camera network is also supplemented by feeds from Axon’s body cameras, as well as drones and public CCTV cameras.

Cameras can be registered on the system without the additional hardware – including home cameras like Amazon Ring devices – to provide police with a list of devices they can canvass after a crime has occurred to find evidence.

Overall crime rates have decreased steadily in the U.S. since the 1990s, according to Pew Research – although the country has seen upticks in both property crime and murders in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The number of public and private surveillance cameras in use grew from 70 million in 2018 to 85 million in 2021, industry research group IHS Markit has found.

The research into the relationship between surveillance cameras and crime is mixed – some studies show that the presence of cameras does result in less crime, while others suggest it merely displaces the activity.

Rialto is betting big on cameras: from 2020 all newly constructed or remodeled commercial and industrial properties in the city were required by the police to register cameras in the Fusus system and allow police to access a live-view, according to the police department.

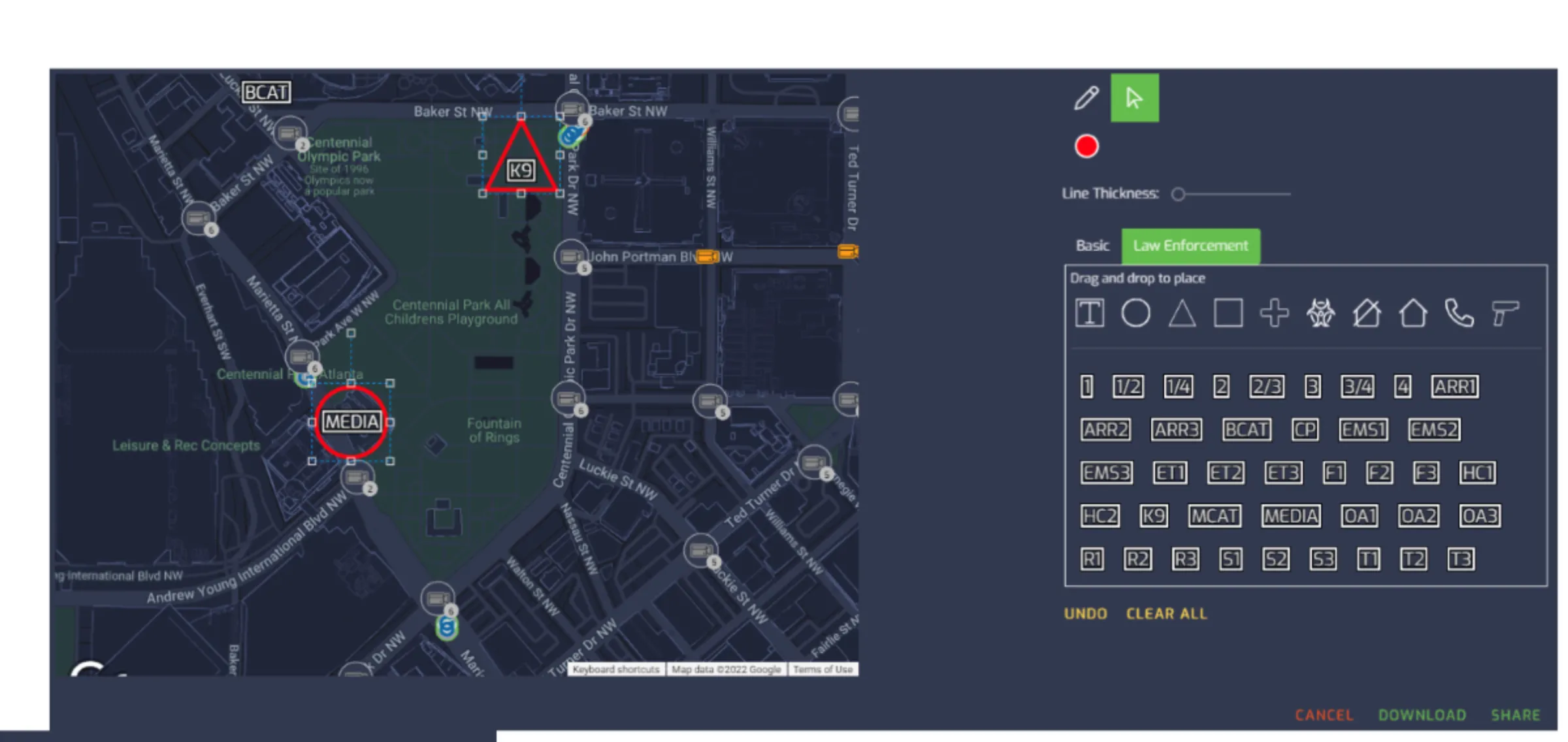

Police in Rialto want to be able to draw a circle on a map of the city, and automatically pull up security camera feeds from cameras in that radius, tracking anyone who moves through those zones.

According to training materials and pitch documents obtained through public records requests, cities can also integrate the Fusus platform with a suite of other big-data policing tools.

These include automatic license plate readers, the gunshot detection tool shotspotter, and predictive policing, as well as AI-powered surveillance tools that allow police to scan the city for specific cars, or people.

A Fusus training document for the Atlanta police department, for example, shows how police can set up an AI-powered “alert” to scan the city for images of a person wearing clothing of a specific color, or holding a bag.

“(Fusus) ambition is pretty grand,” said Andrew Ferguson, a law professor at D.C.’s American University who researches big data policing. “It is to fuse all these big data technologies into one user-friendly system.”

In its whitepaper, Fusus says that “no facial recognition or innate human characteristics” are used or stored in its databases.

In Elizabeth, New Jersey, the Fusus system is integrated with technology from Geolitica, a company formerly known as PredPol up until 2021 which offers “predictive policing” tools.

The Geolitica-Fusus partnership enables what the city calls “virtual patrols”, where police use the predictive algorithm to spotlight parts of the city where the algorithm predicts crime is likely to occur, and tap into nearby cameras, according to a department policy document.

In 2021 investigative news site The Markup analyzed nearly 6 million crime predictions made by PredPol’s algorithm and found that residents of neighborhoods “targeted for increased patrols were more likely to be home to Blacks, Latinos.”

“There was no pubic debate over this – people don’t know they are being tracked in this way” said Nedia Morsy, organizing director with immigrant rights group Make the Road, in Elizabeth.

“And it’s hard to see how this doesn’t just increase over-policing in our Black and Brown communities.”

Neither the Elizabeth police department nor Geolitica responded to specific questions about the program. Geolitica has previously called the data that The MarkUp used for its study “incomplete”.

Public safety

For Jay Bhagat, the owner of a gas station in Rialto that is hooked into the Fusus network, knowing the police can tune in live provides peace of mind. “Before Fusus our employees were afraid of doing the night shift,” he said.

Community engagement officers have been visiting local businesses to explain that enrolling in Fusus will make it easier for police to detect and remove unwanted people from the premises.

“This saves us time,” explained Bhagat, who set up the system early this year after a string of shoplifting incidents, and now can easily share the footage with the police.

For Martinez, “there is no right to privacy in these areas – they are public places”.

Not all business owners see it that way. Sarah Johnson, the owner of an aquarium store in Columbia, Missouri, campaigned against the Fusus rollout in the city, voicing concerns that the police could abuse access to the camera network.

“The people could easily target groups of people – minorities, unhoused people in our community,” she said.

In late 2022, the Missouri city council rejected a proposal to adopt Fusus tech after significant community pushback.

Pat Fowler, a member of the city council who voted against adopting Fusus, said she was not convinced that more surveillance would lead to greater public safety.

“We asked Fusus: exactly what kind of crime are you trying to solve with this? Show us data that it works. But they wouldn’t produce any,” Fowler said.

Fusus did not respond to questions about how it measures efficacy of its tools.

The company publishes case studies on its website highlighting instances where police were able to apprehend suspected criminals with the help of Fusus-linked cameras.

A blog post from April credits Fusus tech for helping police increase the percentage of crimes solved in a number of cities, including Atlanta, Georgia, Rocky Mount, North Carolina, and Bay County, Florida.

In a study published on its website in 2022, Fusus cites a single crime statistic from Jackson, Mississippi – saying that a 51% reduction in crime can be attributed to the introduction of the Fusus platform in the city.

The Jackson police did not respond to requests to clarify the relationship between Fusus tech and the crime rate, but in 2020 the police told NBC News that a 51% crime reduction was linked to new public cameras, before the city launched the Fusus platform.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), an advocacy group, has been monitoring the implementation of Fusus tech across the country, and has shared public records of Fusus contracts from dozens of cities with the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“You walk down the street, out of your house, to the movies, or to your lawyers office, there are now cameras everywhere,” said Adam Schwartz, a senior staff attorney at EFF.

“These business-police partnerships are placing us all under a microscope as we go about our lives: any community considering Fusus should really think again.”

Public debate

In many cities where the Fusus platform has been adopted, critics say there has been little to no public debate. In 2021, the city of San Gabriel, California, voted to adopt the technology in a meeting with no public comment.

Maggie Ullman, who chairs the environment and public saftey committee in Asheville, North Carolina, said the city’s decision to adopt the Fusus system early this year was driven in part by serious staffing shortages in the local police department.

The camera network will allow the police to have more eyes on the ground, she said, adding that before she voted to approve the roll-out, she was assured that the platform would not employ facial recogntion technology.

“So many homes and business have chosen to have cameras installed,” she said. “We need to be creative and willing to take risks within reason for our public saftey.”

Privacy advocates worry about a general lack of oversight.

Ferguson, the law professor, reviewed draft policies governing the use of the Fusus system in South Bend Indiana, and Columbia, Missouri, as well as the “virtual patrol” program in New Jersey.

“These policies are woefully inadequate thinking through the harmful issues of race, privacy rights, and First Amendment rights of citizens,” he said.

They do not spell out what the punishment might be for officers who abuse the system, or what role the surveillance systems will have in monitoring political activities, such as public protest, he explained.

In some places – including Rialto – the police have not drawn up any specific policies to govern the usage of Fusus tech.

When the city of San Gabriel adopted the system in 2021, police chief Gene Harris told the city council that one of the reasons he recommended the product was that he had seen it “field-tested” in Minneapolis the previous year during Black Lives Matter protests.

“If they are public activities then there is a right to monitor, film, document,” Harris, who is now the chief of police in Pasadena, California, said in emailed comments.

The Minneapolis police department did not provide responses to a list of questions about its Fusus program.

Schwartz of EFF said he is concerned about law enforcement using Fusus tech to monitor demonstrations and public protests.

“If you put surveillance tech like this in the hands of police, they will turn it on protests, on political activity such as the Black Lives Matter movements,” he said. “That’s what history shows us – and that has a tremendous chilling effect on democratic activities.”