Exclusive: Historians had previously thought that such operations were much less extensive

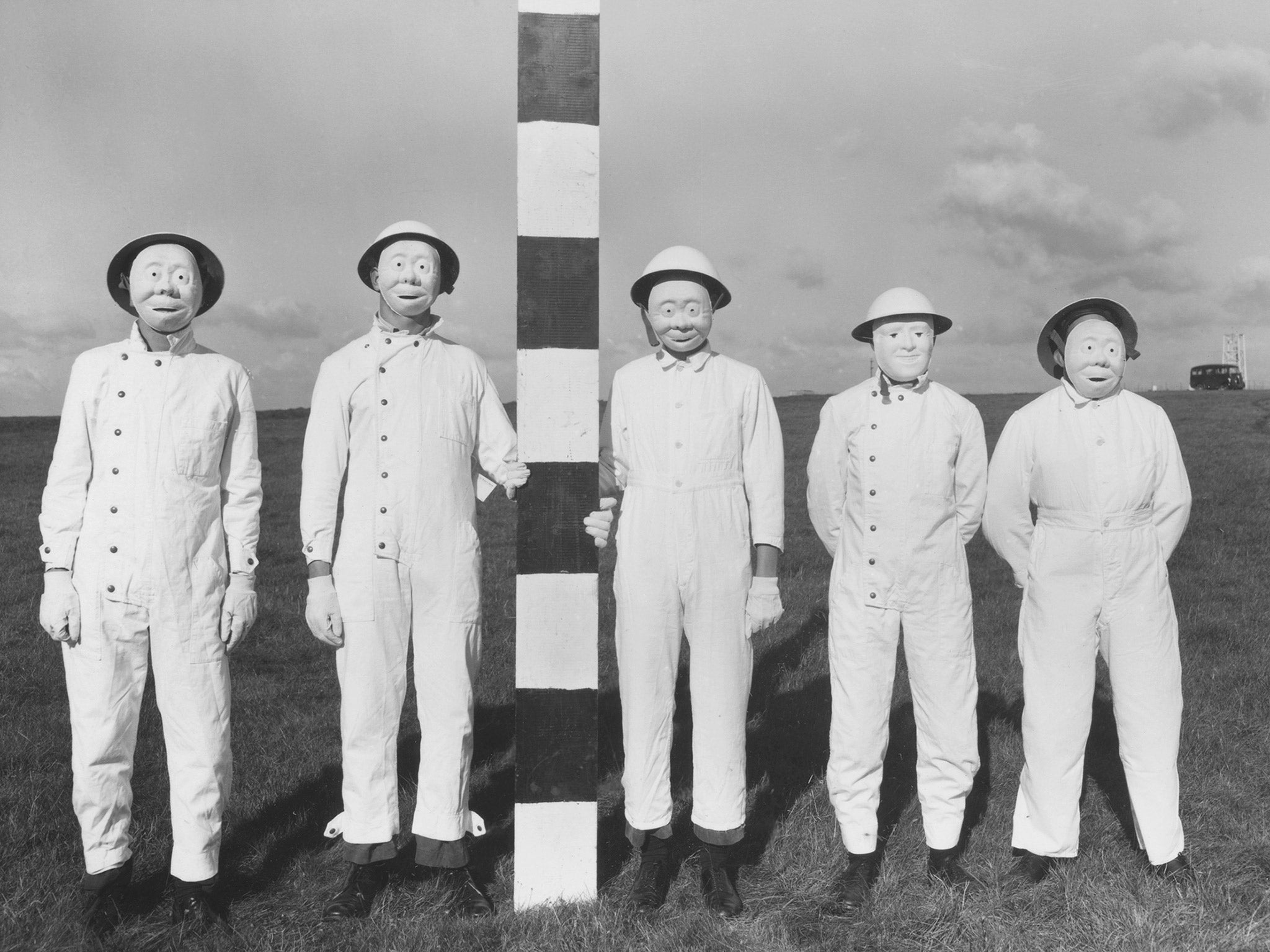

Field trial personnel in 1956. The masks had to be worn to allow the collection of proxy warfare substances that had been sprayed from aircraft

During the Cold War, the British Government used the general public as unwitting biological and chemical warfare guinea pigs on a much greater scale than previously thought, according to new historical research.

In more than 750 secret operations, hundreds of thousands of ordinary Britons were subjected to ‘mock’ biological and chemical warfare attacks launched from aircraft, ships and road vehicles.

Up until now historians had thought that such operations had been much less extensive. The new research, carried out by Ulf Schmidt, Professor of Modern History at the University of Kent, has revealed that British military aircraft dropped thousands of kilos of a chemical of ‘largely unknown toxic potential’ on British civilian populations in and around Salisbury in Wiltshire, Cardington in Bedfordshire and Norwich in Norfolk.

Substantial quantities were also dispersed across parts of the English Channel and the North Sea. It’s not known the extent to which coastal towns in England and France were affected.

The research reveals, for the first time, that around 4600 kilos of the chemical, zinc cadmium sulphide (now thought to be potentially carcinogenic, on account of its cadmium content) were dispersed from ships, aircraft and moving lorries between 1953 and 1964.

Professor Schmidt’s investigation – published on 9 July as a book, Secret Science – has revealed that commuters on the London underground were also used as guinea pigs on a substantially larger scale than previously thought.

The new research has discovered that a hitherto unknown biological warfare field trial was carried out in the capital’s tube system in May 1964.

The secret operation – carried out by scientists from the government’s chemical and biological warfare research centre at Porton Down, Wiltshire – involved the release of large quantities of bacteria called Bacillus globigii. The scientists were keen to discover whether ‘long distance travel of aerosols’ in the tube network ‘was due to transportation within trains’ or through the tube’s air ventilation systems.

At the time, the government thought that Bacillus globigii bacteria were harmless – but they are today regarded as a cause of food poisoning, eye infections, and even septicaemia. It is not known whether the authorities attempted to properly test the bacterium before releasing it into the tube system. An earlier series of tube field trials, in July 1963, has been known to historians for many years.

However, the new research has now revealed that some of the British scientists involved had grave misgivings about the field trials that had been carried out. Indeed some had long felt that it was not politically advisable to conduct large-scale trials in Britain with live bacterial agents.

One particular test – involving live plague bacteria – was carried out off the west coast of Scotland in 1952. It’s long been known that a fishing vessel inadvertently passed through the cloud of bacteria and that the authorities were very worried that the fishermen might contract the disease.

The plague bacteria field trials, though at sea, took place only a few miles from the Isle of Lewis which had a population of several thousand.

The government scientists, carrying out the trials, banked on the fact that the prevailing wind normally blew away from the coast. If, however, the wind had changed direction, thousands of Hebrideans would have been at risk from plague infection, says Professor Schmidt.

Following the fishing vessel incident, the scientists were eager to carry out any further potentially very hazardous field trials outside the UK. Prime Minister Churchill therefore approved a plan to carry out tests in a British overseas territory, the Bahamas.

New research shows that the government scientists took the view that the Bahamas was the best place “on the surface of the globe” to carry out tests “without restrictions”.

In 1954, the British government sent Cold War biological warfare scientists to an area of sea near an uninhabited island in the Bahamas to release clouds of dangerous Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis viruses. These organisms were capable of causing, in humans, high fever, long term fatigue, headaches and occasionally death.

The new research reveals, for the first time, that in another British imperial possession, Nigeria, a location was found for chemical warfare field trials. In an area called Obanaghoro in southern Nigeria, four British Cold War scientific missions spent a total of around 15 months dispersing, and assessing the effects of, large quantities of experimental nerve gas weapons. The advantage of the location was that it permitted field trials to be carried out in a tropical environment – and, of course, that it was not in Britain or Australia.

The extent that local people (including locally employed field trial personnel) were affected by the nerve agents is not known.

Historians have so far been unable to find out who did the particularly hazardous work of ‘hand-charging’ the nerve agent artillery shells, mortar bombs and aircraft cluster bombs. Likewise they have not been able to discover the extent to which local Nigerian soils were contaminated or whether nearby villages and schools were affected by any of the toxic clouds that would have been blown across the countryside.

“The government records I’ve been looking at are conspicuously silent on all this,” said Ulf Schmidt.

“Officials had clearly good reasons as to why the kind of experiments undertaken in Nigeria were strictly prohibited on the British mainland, which is why the files and photographic records surrounding Britain’s post-war nerve agent testing in Africa were regarded as particularly sensitive,” he said.

Professor Schmidt’s research has also revealed the vast scale of Cold War chemical warfare tests carried out on ‘volunteer’ British service personnel here in the UK – involving numbers of people much greater than previously thought.

His investigation now suggests that up to 30,000 secret chemical warfare substance experiments were carried out, mainly at Porton Down, on more than 14,000 British soldiers between 1945 and 1989. He believes that, in most cases, the servicemen were not given sufficient information to allow them to give properly informed consent.

Ulf Schmidt’s book, Secret Science, is published by Oxford University Press.

Spreading diseases: ‘Harmless’ proxies

Aircraft, lorries and ships spread 4,600kg of cadmium sulphide in one decade

Zinc Cadmium Sulfide ultra-fine particles. This inorganic compound was used by Cold War scientists in the UK and the US as a supposedly harmless proxy to simulate the behaviour, in the lower atmosphere and on the ground, of biological warfare substances. However it is still not known whether particles of ZCS that may have become embedded in people’s lungs for decades could ultimately cause disease.

Bacillus globigii. This bacterium was used as a supposedly harmless proxy to simulate the behaviour, in terms of dispersal and penetration, of biological warfare aerosols. Although not considered harmful when it was used in Cold War field trials, it is now known to be capable of causing fevers, food poisoning (occasionally resulting in death), peritonitis and septicaemia .

Pasteurella pestis (now known as Yersina pestis). Clouds of this highly infections bacterium were dispersed only over areas of sea – but nevertheless very near to Lewis, a Scottish Island with thousands of inhabitants. In order not to infect the islands, it appears that the scientists relied entirely on the wind not changing direction and speed. This bacterium is the one that has caused plague epidemics worldwide in the past (including those of the medieval world’s Black Death).

Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis. Clouds of this virus were dispersed over an area of sea close to an uninhabited island in the Bahamas. The virus debilitates or kills horses and donkeys and can also cause severe fever and even death in humans. Mosquitos spread the virus further by biting equines.

G-series nerve agents. Clouds of this chemical warfare weapon were dispersed during field trials in a small part of southern Nigeria, some miles north of the town of Warri. G-series nerve agents were first developed by the Nazis before and during World War Two. The group includes substances like sarin and attacks the human nervous system, causing loss of bodily function and normally death. Survivors are likely to suffer long-term neurological damage and psychiatric disorders.