The recommendations of the RBA Review are designed to kill government oversight over the nation’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of Australia; destroy the final traces of the powers of the people’s bank, the Commonwealth Bank, retained by the RBA; and set in concrete the austerity agenda that will protect the current financial order at the people’s expense in the coming crisis.

In terms of the main operations of central bank policy, the RBA Review panel, stacked with Bank of England and Bank of Canada honchos and an economics professor, recommends no substantive change. Notwithstanding various criticisms, it in fact affirms that the bank’s key objectives, targets, and current mode of operating amount to the best approach. The big picture changes proposed by the Review relate to mechanisms the RBA does not currently use. The Review’s recommendations are designed to outlaw, in a time of crisis, possible government direction of the RBA, and by extension, direction of the private banks, to protect the citizens of Australia—a relevant function, given the bank is a publicly owned institution which serves the government and the nation.

In 1959 the Menzies government split off the RBA as a separate central bank from Australia’s national bank, the Commonwealth, marking the first step towards the Commonwealth Bank’s privatisation. The changes recommended by the RBA Review relate to functions that were carried over from the Commonwealth Bank. Notably, as the Review admits, those “hangover” powers have never been used, but indications that they might be utilised under crisis conditions by a government responding to necessity and popular demand, was enough: The task of the RBA Review was to pre-emptively crush those powers.

In March 2021 Senators from the Greens, One Nation and the Liberal National Party started pushing the RBA to use those powers—still contained in its governing legislation, the Reserve Bank Act 1959—for the economic benefit of the nation. By September that year the IMF and OECD were suggesting a review of Australian monetary policy. Then-Shadow Treasurer Jim Chalmers committed Labor to a review and by the end of 2021, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg had indicated it would proceed after the (May 2022) election.

Unused powers cannot stand

In Senate Estimates sessions in 2021-22 featuring RBA leaders Guy Debelle, Philip Lowe and Michelle Bullock (documented in our submission to the RBA Review, available at citizensparty.org.au), the Senators kept pressing for the following powers to be used:

- The government has the ultimate say over monetary and banking policy (Section 11, RBA Act)

- The RBA can direct lending into specific areas of the economy (Section 36, RBA Act)

- The government can borrow from the RBA to invest in the economy (by extension of Sections 11 and 36)

Point 1, alone, of the Review’s recommendations undoes all of that and more.

The current objectives of the RBA are: the stability of the currency of Australia; the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia.

The Review’s Recommendation 1 would “Affirm the RBA’s independence and clarify its statutory monetary policy objectives”:

1.1 The RBA should continue to have operational independence for monetary policy. The Government should remove the power of the Treasurer to overrule the RBA’s decisions.

1.2 The Government should amend the Reserve Bank Act 1959 such that:

- The RBA has dual monetary policy objectives of price stability and full employment.

- The “economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia now and in the future” is an overarching purpose for the RBA rather than a separate objective for monetary policy.

1.3 The Government should remove the RBA’s power (in the Banking Act 1959) to determine the lending policy of banks.

Perhaps the most incriminating change proposed by the Review is that the RBA should no longer take the “economic prosperity and welfare” of Australians into account as this mandate “provides too much discretion to the RBA”. It further claims that “monetary policy tools have limited power to directly affect” the welfare and prosperity of Australians. Australian mortgage holders would beg to differ.

In a 20 April press conference Treasurer Jim Chalmers declared the government’s in-principle support of all 51 recommendations (in 14 categories), referring to the following primary policy shifts:

“We intend to introduce legislation to reinforce the independence of the RBA by removing the government’s right to veto its decisions; we intend to introduce legislation to strengthen the RBA’s mandate and clarify that our monetary policy framework has dual objectives of price stability and full employment; and we also will seek to establish separate Monetary Policy and Governance Boards to strengthen expertise, decision making and bring us more into line with world’s best practices.” (Emphasis added.)

Inflation and employment

The second recommendation purports, falsely, to elevate full employment as an RBA objective:

2.1 Equal consideration should be given to price stability and full employment in setting monetary policy.

This concerns the fact that the RBA mandate to maintain full employment has, over recent decades, been completely eclipsed by price stability, a.k.a. “controlling inflation” as the Review puts it.

Yet price stability has never officially been the singular objective of the RBA—it was adopted with the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s-90s, with the intention to block government spending for nation building such as that initiated by the Whitlam government in the early 1970s. As the fight against inflation took over, the RBA was not able to uphold its explicit mandates to ensure the “maintenance of full employment” and “economic prosperity and welfare of the people”. Its only regard for unemployment was ensuring it didn’t go so low as to fuel inflation (today this is reflected in the NAIRU, the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or the owest “sustainable” rate of unemployment).

For context, New Zealand launched a review of its Reserve Bank in 2017, and in 2021 a new RBNZ Act was legislated. It also elevated employment as an equal objective to price stability—but unlike in Australia, its governing legislation did not previously mention employment as an objective. The real purpose of the NZ review, also couched in terms of providing greater transparency and accountability, was to usher in farther reaching “bail-in” powers to save collapsing banks by stealing depositors’ and investors’ money (“New Zealand backflips on statutory bail-in”, AAS, 19 Jan. 2022). This was also demanded of Australia by the IMF, which in its February 2019 Financial System Stability Assessment for Australia demanded a fully legislated bail-in regime in which elected politicians cannot interfere. (“IMF demands end of democracy in Australia’s banking system, full ‘bail-in’”, ACP Media Release, 4 Mar. 2019.)

Dovetailing with this agenda is the RBA Review’s assessment that the RBA’s independence and aims be redefined to “put the RBA’s financial stability role on a firmer footing and strengthen cooperation arrangements with other agencies involved in financial stability”. This should be enshrined in legislation, said the Review, so the RBA can fully cooperate with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA, which oversees bail-in as a means to protect financial stability) in its role, and other regulators. It added that the government’s ability to “override decisions of the Reserve Bank Board … detracts from the independent operation of monetary policy and the credibility of the monetary framework”. In the spirit of outsourcing crucial decisions to unelected technocrats, the Review calls for an expert Monetary Policy Board to be established, plus an external expert advisory group.

In a 20 April press statement, LNP Senator Gerard Rennick declared: “This is just handing power over to unelected bankers and other ‘experts’ who will quite often be nothing but lackeys.” Greens Senator Nick McKim declared that “independence is being prioritised over accountability, and Australia is being asked to bow ever more deeply at the feet of the market.” (Recall that Chalmers in his January essay on “values-based capitalism” had made a big show of demanding “economic inclusion”.) Referring to the push to remove democratic oversight of the bank, McKim added, “the first recommendation is everything Milton Friedman dreamed of.” Indeed, it was economist and Mont Pelerin Society co-founder Friedman, as an external expert advisor to the 1981 Campbell Committee Financial System Inquiry, who was the architect of RBA independence and the deregulation of our banking system in the first place.

Government credit and RBA lending: Sections 11 and 36

The Review recommends whittling back any RBA powers that could be used for the greater good. Recommendation 1.3 calls for “Removing the power to direct lending policies of private banks”, which is possible under Section 36 of the Banking Act 1959. Prudential regulation was handed to APRA in 1998, and therefore, “The RBA does not need, nor should have access to, powers that enable it to direct the lending activities of banks”—something which the Senators have been pushing it to use to rein in the housing bubble and support the real economy, a legitimate central bank function.

The primary purpose of crushing government control over the RBA is to block a crisis-driven revival of national credit. Whitlam’s Treasurer Jim Cairns in 2003 insisted that his government could and should have borrowed from the RBA through Treasury Bills, just as in WWII the Curtin-Chifley government had borrowed from its predecessor, the Commonwealth Bank. (“Cairns: We should have borrowed from RBA not overseas”, AAS, 13 Mar. 2022.)

There should be nothing preventing this today. As pointed out by Senator Rennick during a 6 April 2022 estimates hearing, the RBA already issues credit into the economy via its quantitative easing, Term Funding Facility and bond buying programs. The issue is whether this existing funding can be directed into productive sectors.

Rennick asked RBA Deputy Governor Michele Bullock what the RBA would do if “if the government directed [it] to create money through a quantitative easing program to build infrastructure”. After a lengthy back and forth, Ms Bullock finally answered: “If the government directed us to do that, that is a conversation that would have to be had.”

She answered thus because the RBA is aware of the monetary policy dispute resolution mechanism in its governing legislation. Section 11 in the 1959 Act outlines a procedure which ultimately allows the government to “determine the policy to be adopted by the Bank”.

Section 36 is another pathway to direct credit issued by the RBA to worthwhile pursuits rather than blowing up asset bubbles. In a 16 February 2022 hearing, Senator McKim pointed to the RBA’s power contained in S.36 to direct the class of loans (advances) that banks can make.

Both of these powers were retained from the original Banking Act 1945, which derived from the declaration of the 1937 banking royal commission which resolved a dispute between the Scullin-Theodore government and the Commonwealth Bank governor over issuing credit, by confirming that the elected government is the ultimate authority in the financial system. (See “Foreign interference in banking crushed Australia before—don’t allow a repeat!”, below.)

The tell: pulling legislative punches

The Review panel knows the murky waters it is wading into. While it says “legislated changes should commence on or after 1 July 2024”, and an updated Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy—which Chalmers deliberately delayed for this process—be agreed between the RBA and the Treasurer by the end of 2023, it then pulls its punches. It says that while new legislation is required for the best outcome, it supports legislative change “only if the process can be expected to proceed without putting these principles at risk”, i.e., without backfiring and sparking a broader debate about putting democracy ahead of the decisions of central bank technocrats. This is what happened with the bail-in proposal in NZ. Within six months of the announcement of new banking legislation (the Deposit Takers Act) in April 2021, the government dropped the bail-in section, fearing it would result in a political backlash that would hold up the entire bill.

The RBA Review has therefore dictated that bipartisan support for legislative changes be achieved before any parliamentary process is initiated. It also caters for the possibility that a bipartisan consensus to ram through the required legislative change is not achieved, providing an alternative pathway. This involves composing a new Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy to clarify key issues including central bank independence, “including a statement that the Government will not use its overrule power and the RBA will not use its power to determine the lending policy of banks.”

Chalmers may have secured the support of his counterpart, Shadow Treasurer Angus Taylor, but that is yet to be tested. The RBA clearly understands that the popular reaction will be brutal, but they may not have accounted for the ACP and collaborators, who will fight to block bipartisan support and defeat this legislative assault on democratic accountability for the financial system!

Foreign interference in banking crushed Australia before—don’t allow a repeat!

Under a huge post-war debt burden and depression conditions, the government of Labor Prime Minister James Scullin (1929-32) started its term from an impossible position. The political situation in the parliament was not conducive to the significant financial reforms the Labor Party aspired to, which included the nationalisation of banking. (The political situation is summarised in “Ted Theodore’s fight for a national bank”, AAS, 9 Nov. 2022).

Scullin and his Treasurer Ted Theodore attempted to regain control of the Commonwealth Bank from early 1930 as a vehicle to grow the economy, but quickly met with the opposition of the private trading banks. Despite having little chance of achieving its legislative agenda, the Labor Caucus continued to push for controlled credit and currency expansion to boost production and get people back to work—three in every ten men were unemployed.

Amid turmoil in his own party, Theodore proposed an £20 million “fiduciary note issue”, instructing the Commonwealth Bank to issue new notes, to be spent on agriculture and infrastructure.

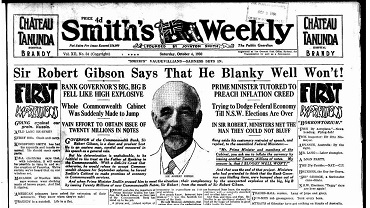

Throwing up fears of inflation, Gibson responded: “Mr Prime Minister and members of the Cabinet, you ask me to inflate the currency by issuing another 20 millions of notes. My answer is that I bloody well won’t.”

Given that the bank was a public entity directed by the government, Gibson should not have had a leg to stand on. But his pronouncement was in line with the findings of the infamous Premiers’ Plan. This, and the increasing prominence of professional economists in departments such as the Treasury, forced a compromise.

Not least because in 1930 Scullin had agreed to a financial mission from Bank of England representatives who conducted the survey of the state of the Australian economy and public finances which resulted in the Premiers’ Plan. That mission, commencing in July 1930, was led by Sir Otto Niemeyer, who through the Bank of England and the League of Nations had designed the austerity programs that led Austria and Italy, and later Germany, down the pathway of financial chaos, resulting in Fascism and Nazism. (Read “The Genesis of Austerity” series available at citizensparty.org.au/australian-alert-service-feature-articles/economic)

Niemeyer delivered his report at a Melbourne conference of Commonwealth government ministers and state premiers in August 1930. His “prescription was ruthlessly deflationary”, wrote L. F. Crisp in Ben Chifley (Longmans, 1961).

The Plan cut public service salaries, pensions and other “adjustable government expenditure” by 20 per cent (but reduced already inadequate old age pensions by “only” 12.5 per cent), made 22.5 per cent reductions in the interest rates paid on government bonds held inside the country and in bank interest rates, reduced private mortgage payments and raised taxes.

Gibson and the banking community were fortified by these prescriptions.

In line with the globally sanctioned policy of deflationary austerity, early in 1931 Chairman of the Commonwealth Bank Board, Sir Robert Gibson, wrote to Theodore demanding “adequate and equitable reductions in all wages, salaries and allowances, pensions, [and] social benefits of all kinds”. He proposed a committee of the government, Commonwealth Bank and private banks to oversee and advise on economic matters. The private banks weighed in, stating they “cannot agree with all the methods suggested by the Treasurer as … these are not on sound banking and economic lines.”

Theodore fired back, in a public speech: “The powers of the organised banks in Australia are used to dictate the Government’s economic policies, financial policy and even its industrial policy. Those great financial institutions have arrogated to themselves a political power that should not be in their possession. They have no mandate from the people to wield the power which they have wielded.”

Nonetheless, the Premiers’ Plan was finally agreed to in June 1931 and passed with bipartisan support. MP John Curtin protested that “Federal Labor has been led into the mud of a moral coalition, involving retraction of all we have said, and entire agreement with all that the Money Power has proclaimed.” Then-Minister for Defence Ben Chifley called for “a more advanced system of extending credit to meet the commercial needs of the community”, foreshadowing “a revolutionary change in the world’s monetary policy” within a decade.

The fight over financial sovereignty would continue to build, with Curtin and Chifley taking the point on the need to return to a Commonwealth Bank with the full powers of government-directed national credit.

The 1935-37 Royal Commission on Banking was called in response to Gibson’s refusal to follow government orders during the Great Depression. The standoff had led to a split in the Scullin government, which lost office to the United Australia Party formed by Joseph Lyons and Robert Menzies. With the depression grinding on, in November 1935 Prime Minister Lyons appointed a royal commission to inquire into the appropriate role of a government bank, and whether the ultimate authority in financial matters should be the elected government or the banks; Chifley, at the time not holding elected office, represented the labour movement on the commission.

The commission ruled that the elected government is the ultimate authority in the financial system, not the banks. “The Federal Parliament is ultimately responsible for monetary policy, and the Government of the day is the executive of the Parliament.” It further found that in a dispute between the government and the Commonwealth Bank board, the government’s view must prevail. Upon taking office as Prime Minister in 1941 Curtin immediately took advantage of this ruling to finally gear up the economy, using war powers to deploy the Commonwealth Bank. They were later permanently enshrined in the Commonwealth Bank Act 1945 (and retained to this day in the superseding Reserve Bank Act 1959). These principle of democratic control over the banking system would be totally at odds with the neoliberal tenets of financial deregulation taken up in the 1980s as with the current proposal by the RBA Review to remove the government’s powers to direct the Reserve Bank.