AI tech makes it trivial to generate harmful fake photos from a few social media pictures.

If you’re one of the billions of people who have posted pictures of themselves on social media over the past decade, it may be time to rethink that behavior. New AI image-generation technology allows anyone to save a handful of photos (or video frames) of you, then train AI to create realistic fake photos that show you doing embarrassing or illegal things. Not everyone may be at risk, but everyone should know about it.

Photographs have always been subject to falsifications—first in darkrooms with scissors and paste and then via Adobe Photoshop through pixels. But it took a great deal of skill to pull off convincingly. Today, creating convincing photorealistic fakes has become almost trivial.

Once an AI model learns how to render someone, their image becomes a software plaything. The AI can create images of them in infinite quantities. And the AI model can be shared, allowing other people to create images of that person as well.

John: A social media case study

When we started writing this article, we asked a brave volunteer if we could use their social media images to attempt to train an AI model to create fakes. They agreed, but the results were too convincing, and the reputational risk proved too great. So instead, we used AI to create a set of seven simulated social media photos of a fictitious person we’ll call “John.” That way, we can safely show you the results. For now, let’s pretend John is a real guy. The outcome is exactly the same, as you’ll see below.

In our pretend scenario, “John” is an elementary school teacher. Like many of us, over the past 12 years, John has posted photos of himself on Facebook at his job, relaxing at home, or while going places.

These inoffensive, social-media-style images of “John” were used as the training data that our AI used to put him in more compromising positions.

Using nothing but those seven images, someone could train AI to generate images that make it seem like John has a secret life. For example, he might like to take nude selfies in his classroom. At night, John might go to bars dressed like a clown. On weekends, he could be part of an extremist paramilitary group. And maybe he served prison time for an illegal drug charge but has hidden that from his employer.

We used an AI image generator called Stable Diffusion (version 1.5) and a technique called Dreambooth to teach AI how to create images of John in any style. While our John is not real, someone could reproduce similar results with five or more images of any person. They could be pulled from a social media account or even taken as still frames from a video.

The training process—teaching the AI how to create images of John—took about an hour and was free thanks to a Google cloud computing service. Once training was complete, generating the images themselves took several hours—not because generating them is slow but because we needed to sort through many imperfect pictures (and use trial-and-error in prompting) to find the best ones. Still, it’s dramatically easier than attempting to create a realistic fake of “John” in Photoshop from scratch.

Thanks to AI, we can make John appear to commit illegal or immoral acts, such as breaking into a house, using illegal drugs, or taking a nude shower with a student. With add-on AI models optimized for pornography, John can be a porn star, and that capability can even veer into CSAM territory.

We can also generate images of John doing seemingly innocuous things that might still personally be devastating to him—drinking at a bar when he’s pledged sobriety or spending time somewhere he is not supposed to be.

He can also be put into fun and fantastic situations, like being a medieval knight or an astronaut. He can appear young or old, obese or skinny, with or without glasses, or wearing different outfits.

The synthesized images are not perfect. If you look carefully, a knowledgeable person can spot them as fakes. But the tech that creates these images has been progressing rapidly, and it may soon be completely impossible to tell the difference between a synthesized photo and a real one. Yet even with their deficiencies, any of these fake images could plant devastating doubts about John or potentially ruin his reputation.

You can see many examples of people using this same technique (with real people) to create whimsical, artistic profile photos of themselves. And commercial services and apps like Lensa have recently emerged that promise to handle the training for you. What they don’t show you is the potential negative effects of this technology if a person uses someone else’s face without their consent.

How does it work?

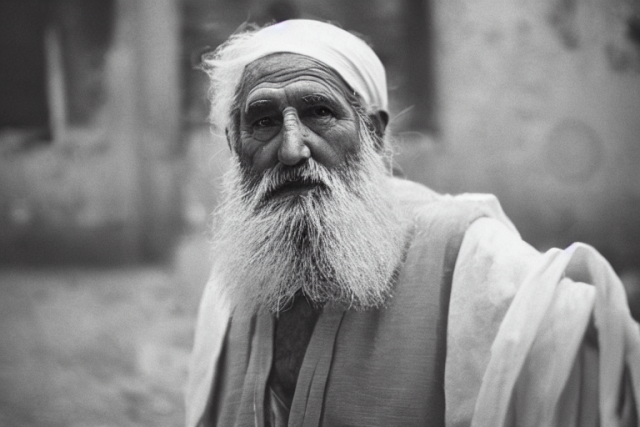

This AI-generated “photo” of ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus pulls from what the AI model knows about photos of old men and depictions of ancient Greek culture that were found in its training data set.

If you haven’t been paying attention to the rapid progress in AI image generators recently, seeing what we’ve pulled off above might be very alarming. Basically, computer scientists have figured out how to generate new photorealistic images of anything you can imagine by teaching AI using real photos, and the technology has accelerated rapidly over the past year.

The tech has been controversial because, aside from photos, it has also allowed people to generate new artwork that imitates existing artists’ work without their permission.

One of the most impactful AI image generators is called Stable Diffusion. It’s a deep-learning image synthesis model (a fancy term for AI software) that can generate completely new images from text descriptions. It can run locally on a Windows or Linux PC with a beefy GPU, on a Mac, or in the cloud on rented computer hardware.

With financial support from Stability AI, an academic organization called CompVis trained Stable Diffusion’s AI model using hundreds of millions of publicly accessible images downloaded from the Internet. Stability AI released Stable Diffusion as open source software on August 22, 2022, meaning anyone can use it for free, and it has become integrated into a growing number of commercial products.

Through intensive training, Stable Diffusion’s neural network has learned to associate words and the general statistical association between the positions of pixels in images. As a result, you can give Stable Diffusion a text prompt, such as “Morgan Freeman in a classroom,” and you’ll get back a completely new image of Morgan Freeman in a classroom.

Making images of Morgan Freeman is easy because there are probably hundreds of photos of him in the data set used to train Stable Diffusion. It already knows what Morgan Freeman looks like. But if you want it to make images of an average person like John, you need to give Stable Diffusion some extra help.

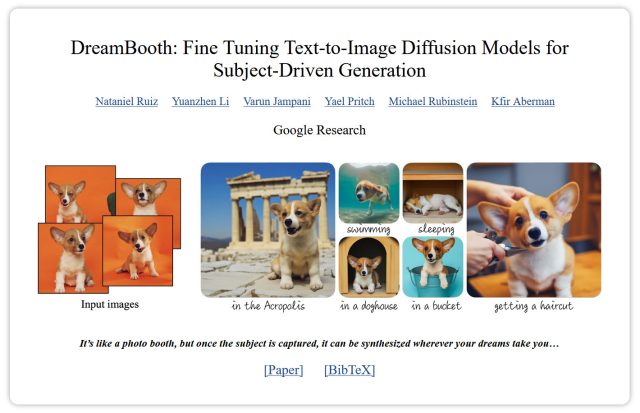

That’s where Dreambooth comes in. Announced on August 30, 2022, by Google researchers, Dreambooth uses a special technique to teach Stable Diffusion’s AI model new subjects through a process called “fine tuning.”

This is absolutely incredible. Also: Now may be your last chance to take down public images of yourself from the Internet before they become manipulated/animated by AI, if you feel particularly at risk https://t.co/ZyOvZLoaDL— Benj Edwards (@benjedwards) August 30, 2022

Initially, Dreambooth had nothing to do with Stable Diffusion, and Google held back the Dreambooth code due to concerns of misuse (like we’ve shown here). But not long after its announcement, someone adapted the Dreambooth technique to work with Stable Diffusion and released the code freely as an open source project.

Since then, Dreambooth has become a popular way for AI artists to teach Stable Diffusion new artistic styles (or about products like shoes), and they share their resulting Dreambooth-tuned models in repositories online. Other artists download them and can use previous Dreambooth training to achieve similar effects.

Google researchers used cute Corgi dogs to illustrate Dreambooth’s capabilities to avoid obvious ethical issues about training AI models with humans.

But from the beginning, Google’s researchers knew that if you can put humans (like John) in any fake situation, trouble might follow. That’s why when they announced Dreambooth, they used pictures of Corgis and not people as examples. Avoiding these potential ethical issues by focusing on images of cute animals has drawn criticism from MIT Technology Review, and it’s an example of how AI scientists often try to minimize or avoid criticism for the potential negative impacts of their research.

Impacts

An assortment of robot portraits generated by Stable Diffusion.

By some counts, over 4 billion people use social media worldwide. If any of them have uploaded a handful of public photos online, they are susceptible to this kind of attack from a sufficiently motivated person. Whether it will actually happen or not is wildly variable from person to person, but everyone should know that this is possible from now on.

We’ve only shown how a man could potentially be compromised by this image-synthesis technology, but the effect may be worse for women. Once a woman’s face or body is trained into the image set, her identity can be trivially inserted into pornographic imagery. This is due to the large quantity of sexualized images found in commonly used AI training data sets (in other words, the AI knows how to generate those very well). Our cultural biases toward the sexualized depiction of women online have taught these AI image generators to frequently sexualize their output by default.

To deal with some of these ethical issues, Stability AI recently removed most of the NSFW material from the training data set for its more recent 2.0 release, although it added some back with version 2.1 after Stable Diffusion users complained that the removal impacted their ability to generate high-quality human subjects. And the version 1.5 model is still out there, available for anyone to use. Its software license forbids using the AI generator to create images of people without their consent, but there’s no potential for enforcement. It’s still easy to make these images.

In a similar vein, children and teenagers could be bullied using this technology, even if their images are not manipulated in a sexual way. A kid’s appearance or location could be altered to humiliating effect and shared with peers.

Is there anything we can do about it?

Right now, you can try to take all your photos offline. Maybe that’s a good idea. But for some people, like politicians or public figures, it’s not feasible. And in other cases, friends may have published photos of you in group settings that are outside of your control.

In the future, it may be possible to guard against this kind of photo misuse through technical means. For example, future AI image generators might be required by law to embed invisible watermarks into their outputs so that they can be read later, and people will know they’re fakes. But people will need to be able to read the watermarks easily (and be educated on how they work) for that to have any effect. Even so, will it matter if an embarrassing fake photo of a kid shared with an entire school has an invisible watermark? The damage will have already been done.

Stable Diffusion already embeds watermarks by default, but people using the open source version can get around that by removing or disabling the watermarking component of the software. And even if watermarks are required by law, the technology will still exist to produce fakes without watermarks.

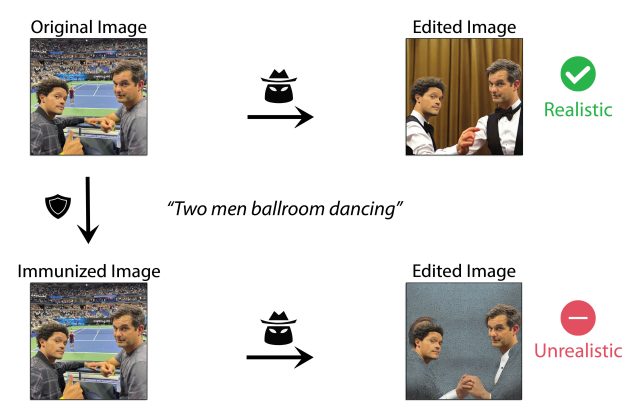

An illustration of MIT’s PhotoGuard process that guards against AI photo editing. A similar adversarial method might prevent AI from being trained on certain images.

We’re speculating here, but a different type of watermark, applied voluntarily to personal photos, might be able to disrupt the Dreambooth training process. Recently, a group of MIT researchers announced PhotoGuard, an adversarial process that aims to disrupt and prevent AI from manipulating an existing photo by subtly modifying a photo using an invisible method. But it’s currently only aimed at AI editing (often called “inpainting”), not the training or generation of images.

Another potential antidote is time. As awareness grows, our culture may eventually absorb and mitigate these issues. We may accept this kind of manipulation as a new form of media reality that everyone must be aware of. The provenance of each photo we see will become that much more important; much like today, we will need to completely trust who is sharing the photos to believe any of them. But during a transition period before everyone is aware of this technology, synthesized fakes might cause a measure of chaos.

While it’s tempting to think that our sense of media reality—even if currently misplaced—may suffer a fatal blow at the hands of synthesized photography, many people already know to be skeptical of photos that could be manipulated or taken out of context. Still, we tend to believe evidence when it supports what we want to believe. In that sense, nothing has changed but the scale and speed at which the fakes can take place.