During the recent election campaign, some minor parties (for example Pauline Hanson’s One Nation and the United Australia Party) advocated against proposed digital identity legislation. The Digital ID system was initiated by the Coalition Government in 2015 as a ‘safe, secure and convenient way to prove who you are every time you access government online services … entirely voluntary and controlled by you’. In October 2021 an exposure draft of a Trusted Digital Identity Bill 2021 was circulated, but the Bill was not introduced before Parliament was prorogued in April 2022. The Coalition’s 2022 election commitments included ‘expansion of the Digital Identity system’, but the Australian Labor Party did not announce a position on the System. However, in a Senate Committee report published in September 2020, Labor senators’ dissenting report indicated that they supported the System but argued for improvements. While it is likely that the System will be progressed during the 47th Parliament, many variables will depend on how the incoming Labor Government responds to criticisms of the System. This Flagpost provides an outline of the System and highlights criticisms about architecture, security, and biometrics.

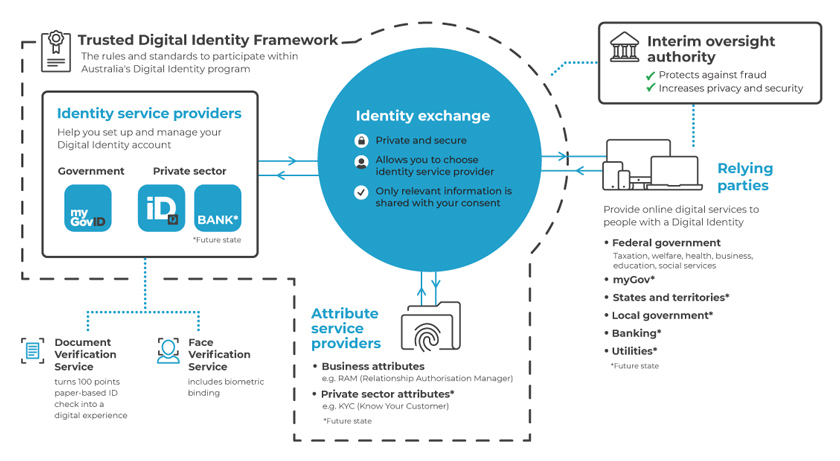

The following diagram represents the complex web of current and proposed internal and external relationships of the Trusted Digital Identity Framework (TDIF) that underpins the System. The draft Bill and material published by the DTA expand on the roles and relationships but, as noted below, the documentation available to date has been criticised for its lack of detail about some aspects, such as biometrics.

The Government’s Digital Transformation Agency (DTA) was responsible for developing the System until May 2021, when responsibility was transferred to Services Australia. The DTA has outlined the purpose of the System:

Digital Identity provides Australian people and businesses with a single, secure way to access government and other services online. … A secure Digital Identity replaces the need for multiple logins to access different services and makes getting things done with government faster and easier. The system will expand over time to include more government agencies as well as private sector organisations.

Creating and using a Digital Identity is not compulsory and is your choice to make. People can still access government services in other ways, such as on the phone or in person at a government shopfront.

The System currently provides access to over 80 services offered by the Australian Government, for example, to apply for a Tax File Number, an online Customer Reference Number, a Unique Student Identifier, or a company director identification number. However, Your guide to the Digital Identity legislation, an explanatory publication circulated by the DTA in a 2021 consultation process, notes that legislative authority is necessary to ‘expand, maintain and regulate’ the System, including to enable state, territory and private sector entities to participate.

Government Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) statements and Budget papers indicate that more than $600 million will have been expended on the System by 2024.

Years. Sources. Allocation ($ millions)

2016–17 MYEFO statement, p. 188. 16.8

2017–18 Budget Paper no. 2, p. 140. 22.7

2018–19 Budget Paper no. 2, p. 167. 92.4

2019–20 Budget Paper no. 2, p. 155. 67.1

2019–20 MYEFO statement, p. 278. 5.9

2020–21 over two years Budget Paper no. 2, p. 66. 256.6

2021–22 over two years MYEFO statement, p. 220. 160.9

2022–23 Budget Paper no. 2, p. 158. 1.8

Total (2016 to 2023). 624.2

In relation to cost-recovery, the DTA notes that ‘Australians will not need to pay to use the System … The charging framework will only apply to businesses and governments who will participate in the System’. However, the charging framework has not been released, and is still under negotiation with stakeholders.

Throughout the System’s development, numerous commentators have highlighted concerns. For example, in her submission to a consultation process in 2021, Sydney Law Professor Kimberlee Weatherall criticised the proposed system architecture, arguing that ‘the system should be framed, not as a digital identity system but as a digital credentials system’. In their submission to the consultation, ANU academics Ben Frengley and Vanessa Teague, identified security concerns and concluded that ‘the system should be abandoned and redesigned from scratch by people with some understanding of secure protocol design and some concern for protecting their fellow citizens from identity theft.’

A review commissioned by the Department of Home Affairs in 2018 (but released in May 2022 through a freedom of information (FOI) application), examined how Australian citizens’ identity information is protected and managed, and recommended greater use of biometrics and face verification. However, RMIT academic Kelsie Nabben has observed that System documentation available to date is ‘opaque on details’ about the proposed use of biometric matching. Nabben also observed that available documentation explains little about the System’s use of automated decision-making.

Following an earlier consultation process in late 2020 the DTA released a ‘synthesis report’ that purported to represent the views of the submissions. However this process has also been criticised, with Professor Teague commenting that ‘the synthesis report … completely fails to distinguish between support for the aspiration of a secure digital ID, and support for the DTA’s current design, which I have not heard from a single technically-literate person’. The NSW Council for Civil Liberties further stated that ‘the consultation process for the DIS [Digital Identity System] has been “too little too late”. There has been inadequate time for public consultation over what is a complex and wide-ranging project’.

The next phase in the System’s development will depend on how the incoming Labor Government responds to criticisms of the System, and on the views of Senate cross-bench parties and independents.