The UKHSA might have stopped including information on infections, hospitalisations and deaths by vaccination status in its Vaccine Surveillance Reports, but that doesn’t mean that they’re now devoid of all value. For example, they have for some months included data on the impact of the vaccines on certain aspects of pregnancy, and these data deserve some analysis.

To me, these reports have only served to illustrate the difference between prospective studies and post hoc analysis – in prospective studies it is necessary to state the aspects of the data that will be explored before you know what the results are going to be, whereas in post hoc analysis you have more freedoms to choose the aspects of the data that fit your needs (and ignore those that don’t). Thus it is of no surprise that the data selected by the UKHSA on the impact of the Covid vaccinations on pregnancy have shown there to be no significant effect. Of course, you might find that even with post hoc analysis it sometimes happens that the data that you first thought supported your case later turn out to be less supportive than you imagined, requiring the invention of reasons to stop reporting the data (this recently appears to have happened in both the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report and the Zoe Symptom Tracker study). There’s now evidence that suggests the detail in the pregnancy outcomes data might also be showing inconvenient data (thanks to analysis by I Numero on Substack in this and subsequent posts).

Survival bias

Before I start this analysis remember that, as for general mortality data, the peering into statistics about stillbirth rates hides the personal tragedies behind each individual that contributes to the data. Always be mindful of this, because the numbers themselves hide the reality behind the data.

The data of interest relate to an apparently innocuous sentence in the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report’s pregnancy outcomes section:

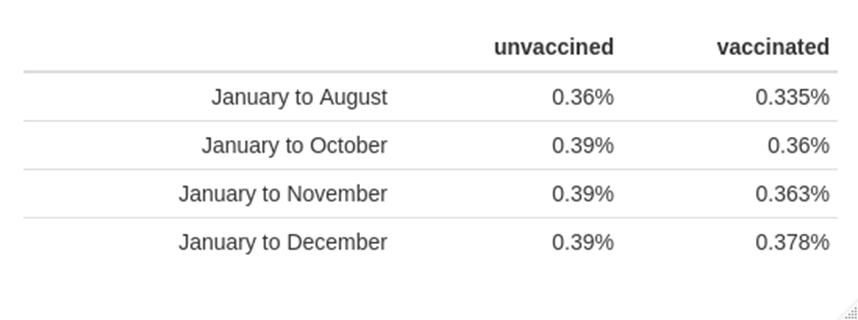

The stillbirth rate for women who gave birth having received one or more doses in pregnancy (3.78 per 1,000, 95%CI 3.41 to 4.19) was similar to the rate for those who had not received any doses in pregnancy (3.90 per 1,000, 95%CI 3.72 to 4.09) giving birth between January and December 2021.

This seems nice and simple – the vaccines don’t seem to increase stillbirth rates by any significant amount, and might even reduce stillbirth rates. Great!

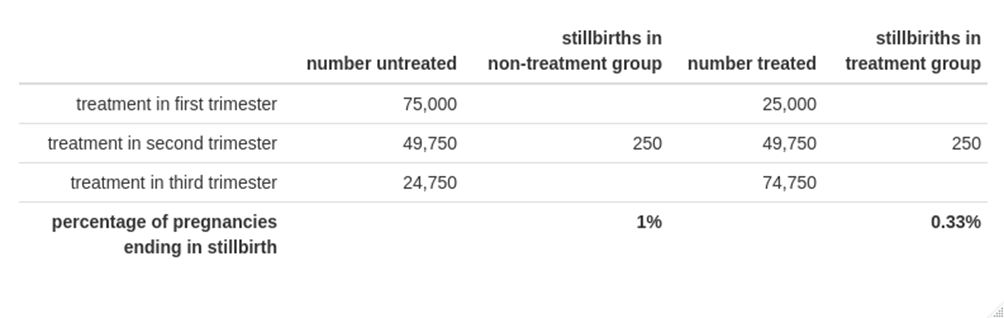

The problem is, during a vaccination campaign, you have to consider that at least some of those women that have tragically suffered a stillbirth didn’t get a chance to get vaccinated later in their pregnancy. This effect is perhaps complex, but it can be illustrated using a simple example. Consider a population of 100,000 women that get pregnant all at once (perhaps after the screening of a particularly engaging movie about cute babies) with a stillbirth rate of 0.5% in the second trimester of pregnancy (specifically), and where one quarter get a medical treatment during their first trimester, one quarter during the second trimester, one quarter during the third trimester and one quarter were still untreated at the end of their pregnancy. Let’s examine how these illustrative pregnancies would proceed.

The result of this? Even though the stillbirth rate in this example is identical for each group, the eventual stillbirth rate is very different between the two groups; these data would suggest that the medical treatment significantly reduces stillbirth rates. This happens because when a non-treated woman suffers a stillbirth, it is added to the tally of stillbirths in the non-treatment group, even if she would have been treated later in her pregnancy; this introduces a ‘survival bias‘ towards stillbirths occurring in the non-treatment group. In order to achieve the same stillbirth rate in this trivialised example it would require the stillbirth rate in the treatment group to be three times higher than the non-treatment group – and this simplistic analysis of the data would then suggest that the treatment was safe even though the actual stillbirth rates were significantly higher.

The real figures are more complex to analyse and in my opinion there isn’t enough data given by the UKHSA to get a firm estimate of the actual discrepancy – but it is very likely that the conclusion reached by the UKHSA is misrepresenting the facts:

It is therefore very reassuring that women who had received at least one dose of the vaccine in pregnancy were more likely to deliver live born babies at term without low birthweight and had no overall increased risk of any adverse outcome through January to December.

I would suggest that the data it presents are by no means reassuring. For reference, I Numero calculatesthat the vaccine group had an excess stillbirth rate of 33% compared with the unvaccinated; I consider that this excess appears plausible given the data that we have access to.

There aren’t many other independent sources of data on stillbirth rates, but one has recently been made available – data on stillbirth rates in Israel was obtained via a freedom-of-information request and has been analysed by Dr. Josh Guetzkow on Jackanapes on Substack. The whole post is worth a read, but to summarise, the data showed that stillbirth rates in the vaccinated were approximately one third higher than in the unvaccinated – surprisingly close to I Numero’s estimate based on an entirely different dataset.

Analysis of the data by month

The UKHSA doesn’t give us monthly totals for much of the relevant data, but it does give an updated percentage for the stillbirth rate since the start of the vaccination programme.

Again, taken at face value these values are ‘reassuring’ as they suggest no significant difference between outcomes in the vaccinated vs the unvaccinated. However, cumulative percentages like this can hide some significant differences. To illustrate this point, consider a person who has average earnings of £1,000 a month over the first 11 months of a year (perhaps he’s a particularly rubbish footballer), but who at the end of the year earns an average of £1,050 over 12 months. That sounds like it isn’t a significant change – but in that 12th month he must have earnt £1,600 in order to get that average of £1,050 over 12 months, significantly more than the £1,000 a month that he’d earnt earlier in the year (perhaps it was a footballer who had scored a lucky hat trick in a game in month 11).

To put numbers on what this means: We have 12 months’ worth of data on stillbirths in the table above. At month 11 in the unvaccinated there had been an average of 390 stillbirths per 100,000 pregnancies, and in the 12th month there must have been an additional 390 stillbirths as the stillbirth rate was unchanged. However, in the vaccinated at month 11 there had been an average of 363 stillbirths per 100,000 pregnancies, but in the 12th month there must have been an additional 543 stillbirths for the average over the 12 month period to have risen to 378 per 100,000 – that’s an increase of approximately 50%.

Note in particular that the final month’s rate for the vaccinated is substantially greater than that in the unvaccinated for the same month, even though the average over the 12 month period remains below the unvaccinated rate – such are the complications of working with cumulative percentages.

Other data

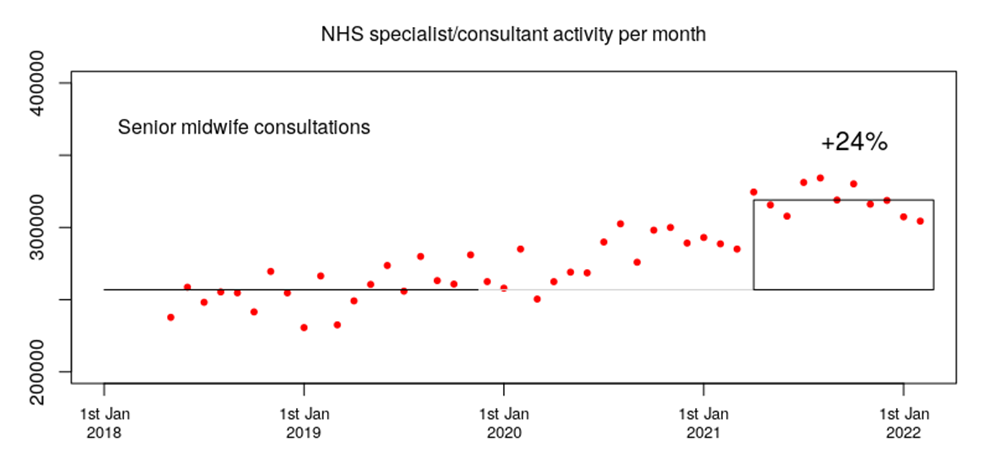

We don’t have much other data to work with on stillbirth rates or, indeed, any other pregnancy outcomes, but one aspect that we do have access to is the number of consultations with senior midwives and how these have changed over the last few years.

Consultations were running at about 250,000 per month prior to 2020, but have risen to over 300,000 per month since spring 2021. That’s a significant rise in consultation rates – and we don’t have a baby boom to explain it.

This isn’t conclusive proof that there’s something going on – there are too many factors at play to make this conclusion (not least whether vaccination during a particular phase of pregnancy is relevant). However, the data that have been made available to us since January 2021 do suggest that there needs to be far more rigorous analysis of the impact of the vaccines on pregnancy.